Worldwide Church of God

Family Tree

Prehistory of the Worldwide Church of God

Among long-

Although not every member of the WCG may have believed this, it was a part of the

culture of the organization. No one could be a “self-

There is not one example in the New Testament showing that any man was ever ordained to an office of authority WITHOUT the hand of man! The ONLY examples and instructions we have show God doing it thru the hand of men of His choosing!... There is no example in the Bible where God carried on HIS WORK under the New Covenant by any single individual OUTSIDE OF, INDEPENDENT OF, HIS ORGANIZED CHURCH AND HIS ORDER OF GOVERNMENT IN THE CHURCH. Anyone outside of God's Church is AGAINST God's Church!

Earlier in the article he explained, “Finally, brethren, though I have mentioned it in the Autobiography, many may not realize the significance of the fact that I personally was fully ORDAINED by the laying on of hands after fasting and prayer of those in authority in GOD'S CHURCH. It was in the summer of 1931.”

(Actually, at different point in his ministry, Armstrong either emphasized or de-

Let’s take a brief look at the pre-

The Seventh Day Baptists

Excerpt from a brief history from a Seventh Day Baptist website:

Seventh Day Baptists date their origin with the mid-

One of those who maintained Sabbath convictions while a member of the Baptist Church in Tewksbury was Stephen Mumford who came with his wife to Newport, Rhode Island in 1664. Through his influence, several members of the First Baptist Church of Newport joined in fellowship with him while remaining members in the parent body. When two couples gave up their Sabbath convictions, the others found difficulties in sharing communion with them in the Newport Church, and a separation took place in December 1671, giving rise to the first Seventh Day Baptist Church in America. Yet after the separation, close fellowship with other Baptist brothers remained, and twenty years later when the Newport Baptist was without pastoral leadership, they voted to place themselves under the care of William Hiscox, the Seventh Day Baptist pastor.

A similar separation occurred in 1705 at Piscataway, New Jersey, when a deacon of the Baptist Church, Edmund Dunham, became convinced of the biblical basis for Sabbath observance. Dunham and sixteen others withdrew to form their own church. A third group of churches came out of the Keithian split from Quakerism in the Philadelphia area about 1700. A pietistic movement among German immigrants was influenced by this third group. This led to the formation of a sister conference known as German Seventh Day Baptists which founded the cloisters of Ephrata, Pennsylvania about 1728. From these beginnings, Seventh Day Baptists followed the westward migration, arriving on the Pacific Coast by 1900.

Notice that there is no mention here of a “historical thread” of Sabbath keeping from Apostolic Times to the 1600s. This is typical of Seventh Day Baptist historical accounts. They make no claim to have inherited the belief in the Sabbath from a group just prior to their own. They view their Sabbatarian beliefs as a “restoration” of apostolic practice, and consider that the men mentioned above came to their convictions about the seventh day Sabbath strictly from their own biblical studies.

Nor is there any apparent conviction that the leaders in the Seventh Day Baptist group received authority from God to exercise their leadership because they received ordination from the hands of any previous Sabbatarians. This would have been impossible, since they didn’t know of any Sabbatarians in the generation before their own.

In an email discussion with a representative of the central organization of the Seventh Day Baptists several years back, I asked about the WCG’s claim that the Seventh Day Baptists were a part of their own “unbroken history” back to the Apostles. He noted:

“We have had in the past some difficulty with the World Wide Church of God who have claimed some of our history and make it theirs in their attempt to establish a kind of “apostolic succession for the Sabbath.” They made an attempt to claim the old meeting house in Newport Rhode Island as theirs because we were the only group that historically were Sabbathkeepers. (In fact the librarian inferred that they practiced exorcism when he said to me “Frankly, they scare the hell out me when they come!”) With the abandonment of the Sabbath [under the regime of Herbert Armstrong’s successor, Joe Tkach, Sr.], they have dropped this attempt. The book by Dugger and Dodd entitled, “The History of the True Church,” is filled with so many inaccuracies and false assumptions that have caused innumerable difficulties.”

No, there is no “smoking gun” that can connect any ministers of the Seventh Day Baptist denomination ordaining any ministers of groups which later “evolved” toward the Worldwide Church of God. The only connection that can be historically documented between the Seventh Day Baptists and the Worldwide Church of God … was a single woman!

Her name was Rachel Oakes Preston, and her story is part of the next chapter of the

Pre-

Adventism

Adapted from the Field Guide History of Seventh Day Adventism

William Miller was a Baptist "lay leader" in New York state who began studying Biblical

prophecy in earnest around 1820, and developed elaborate theories about the timing

of the Second Coming. He attempted at first to present his theories to the ordained

ministers in his area, hoping that they would preach them to the public. But his

attempts to convince others to spread his ideas were mostly ineffective. So in 1831

he reluctantly started preaching about them himself. In 1833 he published his first

official pamphlet on end-

Using an elaborate system of Bible number-

This was back before “Power Point Presentations,” but in the 1830s Miller made good use of the 19th Century version of “flip charts” in a series of lectures given in small towns throughout New England. By the early 1840s, he had graduated to preaching in big city venues.

Conservative estimates indicate Miller and his associates presented his theories

ultimately to hundreds of thousands of people in America (Miller himself claimed

to have spoken to over 500,000 people, in over 4,500 meetings), along with large

numbers overseas, particularly in English-

As people became enamored of his theories that the End of the World was Nigh, and

tried to convince friends and family members, they often found that they were not

welcome in their local church congregation any more. Independent fellowship groups

meeting in homes and rented halls began springing up around the country. Called “Millerites”

by non-

It is now obvious to everyone that Miller’s theories didn’t work out. Jesus didn’t

come in 1843, nor in the spring of 1844. When that prediction failed, Miller tried

moving the date to fall 1844, but when that date failed too, Miller gave up on date-

Two women stepped into this adventist world in 1843.

Ellen Harmon 1827-

Ellen Harmon 1827-

Ellen G Harmon was 16 years old when she and her family, former members of the Methodist

Episcopal Church, made a total commitment to the Millerite movement in that year.

She had first heard Miller’s preach in 1840, and by 1844 was among those waiting

breathlessly for The End to come. When the date passed without Jesus coming back,

Ellen was among those who didn’t give up the hope that He still would soon. By December

1844 she claimed to have received the first of many “visions” from God that would

lead to her, after her marriage to James White, becoming Ellen G White, prophetess

and focal point of the Seventh-

Many don’t seem to realize that William Miller was not a Sabbatarian—he didn’t believe

in the seventh-

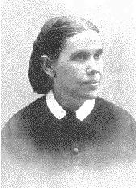

Rachel Oakes Preston 1809-

Rachel Oakes Preston 1809-

Rachel Oakes was originally a Methodist. But in about 1837 she became convinced about the seventh day Sabbath and joined the Seventh Day Baptist church in Verona, New York. The Widow Oakes had a daughter named Delight who taught school in Washington, New Hampshire. In 1843 she moved there to be near her daughter. There was no Seventh Day Baptist church in the area, so she tried introducing the Sabbath idea to a group of adventists who had formed in the area around Miller’s ideas. They were so excited about the prospects of Jesus coming by spring 1844 that they paid little attention to her efforts.

But in Spring 1844, a Methodist adventist preacher named Frederick Wheeler became interested in what she had to share, studied into it, and by March 1844 he began observing the seventh day Sabbath and talking about it to others. In the local group and through the network of adventist groups, Wheeler spread his enthusiasm for this new understanding.

From the Seventh-

After the Great Disappointment in October, 1844, during a Sunday service in the Washington church, William Farnsworth stated publicly that he was convinced that the seventh day of the week was the Sabbath, and that he had decided to keep it. He was immediately followed by his brother Cyrus (who became the husband of Rachel’s daughter Delight), and several others. Thus it was that the first little Sabbatarian Adventist group came into being. The group met for the Sabbath in various homes until 1863, when the Christian Church passed into their hands. Later, Rachel married a man named Preston.

… Either through Rachel Oakes or Wheeler, another Adventist accepted the Sabbath in August, 1844. His name was Thomas M. Preble. Mr. Preble wrote an article in defense of the Sabbath, which appeared in the Adventist paper Hope of Israel, published in Portland, Maine, on February 28, 1845. …

Preble’s article was read by Joseph Bates, a leading Adventist preacher since 1839, and a former sea captain. In May, 1845, Bates traveled to Washington, New Hampshire to check out this group’s teaching on the Sabbath. He stayed up all night with Wheeler discussing the Sabbath. Bates left the next morning and returned to his home in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, where a fellow Adventist asked him, “Captain Bates, what’s the news?” Bates gave this immortal reply: “The news is that the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord our God”

…Rachel met Nathan T. Preston in Washington, New Hampshire and married him. They

lived in the area for many years. Not until the last year of her life did Rachel

join the church that she had helped to influence—the Seventh-

One of the men who soon accepted the Sabbath through the extension of Rachel’s efforts throughout adventist circles was James White. By the time he married Ellen Harmon in 1846, he had become a Sabbatarian, and through him Ellen accepted it also.

Belief in the seventh day Sabbath spread throughout some factions of the adventist world at the same time another factor was being spread. Ellen Harmon White had begun having “visions,” and word of these was making its way around the country. The first came in December 1844, shortly after the Great Disappointment the followed the failure of Miller’s predictions. Published as “A Word to the Little Flock,” it basically said that the “door” to salvation had been shut on the date that Miller had predicted, and only those who were already a part of the adventist movement would be saved when Jesus came back … soon.

From D.M Canright: The Life of Ellen White—Her Claims Refuted 1919

In 1849, Elder White began publishing his first paper, Present Truth. Some numbers were printed in one place, and some in another, for two years.

In 1850, at Paris, Me., he issued the first number of the Review and Herald. In 1852 they moved to Rochester, N.Y. Here he started a small printing office. In 1853 they came as far west as Michigan, where they found scattered brethren; then visited Wisconsin. In 1855 they moved their office to Battle Creek, Mich. This remained the headquarters of the denomination for about fifty years. Gradually large interests were built up here, a great printing plant, the large Sanitarium, the College, the Tabernacle, etc. These were the days of greatest harmony and material prosperity. These were the days when I was most prominent with them, and helped in building all these institutions. Finally Dr. Kellogg and Mrs. White parted company, and he, with the Sanitarium, was separated from the denomination. Then the headquarters were moved to Washington, D.C., in 1903.

After locating in Battle Creek in 1855, for the next twenty-

As the claims for Ellen's visions began spreading among the former Millerites, they soon became a central cause of division within adventist circles. There was an increased enthusiasm toward the idea of forming an actual denomination, but the visions were a sticking point with many.

A number of those who rejected her claims but who clung to the Sabbath doctrine and the adventist emphasis eventually had to pull away from the others and organize their own fellowships. This directly led to the formation of groups adopting the name Church of God, Seventh Day (COG7). A number of small denominations with roots in the COG7 movement of the 1860s still continue to this day. And through those, this eventually led to the Worldwide Church of God and its offshoots.

Those who accepted Ellen's visions went on to form their own official Seventh-

It is sometimes erroneously stated that the Church of God, Seventh Day groups came

out of the Seventh-

Another factor that was reported to be a sticking point for many of them was a choice of an identifying name. Certain individuals and groups absolutely insisted that any denomination formed must carry the name “Church of God” right up front, not a name indicating some doctrinal distinctive such as “seventh day adventism.”

Timeline of the development of the Church of God, Seventh Day, movement

The General Conference of the Church of God (Seventh-

A publication called The Hope of Israel (now The Bible Advocate) was started in 1863,

and this publication extended the influence of the body into other areas. Through

this publication, the doctrines of the second advent and seventh-

Gilbert Cranmer is indeed usually credited with being the Founding Father of the

Church of God, Seventh Day movement. From records of the time, he not only broke

with the group that eventually formed into the Seventh-

Open Letter About Gilbert Cranmer Written by Joseph & Louise Perkins [regarding the events of 1858)

Being requested to state our knowledge of the facts concerning the disputed statement of elder Gilbert Cranmer about the visions of Mrs. White being a test of fellowship, we would say that we resided in Otsego, Michigan at the time he came here to preach, and we distinctly remember his preaching that he had no evidence whatever that the door of the sanctuary closed in 1844. And also that he made an appointment to preach on the same question in four weeks from that time. He came to our house, and while there Mr. Lester Russell came in and asked him if he really meant to say that the outer door of the Sanctuary was still open. In answer, brother Cranmer told him that he had said just what he meant, and that he had no proof to the contrary. Mr. Russell said that he had proof that the outer door of the Sanctuary was closed in 1844. Brother Cranmer asked him the nature of his proof, and he drew from his pocket Ellen G. White's book of visions and said there was his proof.

Brother Cranmer answered, "Perhaps Mrs. White's visions are proof to you, but they are not to me."

Some of the church got very much excited over the course elder Cranmer proposed to

pursue in regard to the "shut-

Elder Cranmer was a powerful speaker, a man of pleasing address and a profound reasoner, active in thought and fearless; but with a tender heart, generous to a fault. In 1869 [six years after the SDA denomination was formed], he published this report on his labors in the Hope of Israel:

The first stop I made was in the town Denver, Newaygo County. Here I preached one week and organized a band of 12 members. From thence I went to another neighborhood, six miles distant among the disciples, preached one week and there a half dozen more stepped out to keep the whole law, as well as the gospel.

From there I came to Ottawa County and preached among the Seventh-

Miss Dillon: The Other Woman

Miss Dillon: The Other Woman

By the early years of the Twentieth Century, the SDA denomination was thriving, but the COG7 groups were still small and scattered. They had, however, made it out to the west coast.

That is where the next influential woman enters the story. Miss Dillon was born in 1891 in Iowa. In 1917 she married her second cousin, and in 1924 they moved to Oregon where her husband got busy seeking his fortune.

While she was visiting her in-

Loma Dillon Armstrong became convinced that Ora Runcorn was correct—the Saturday Sabbath was the proper day of worship. When she shared this exciting discovery with her husband Herbert, he became furious. He wanted nothing to do with religious fanaticism, and even threatened divorce when stubborn Miss Loma refused to let go of her newfound belief. Rather than divorce, he settled on doing his own study of the topic so he could “prove” to her she was wrong. Instead he proved to his own satisfaction she was right.

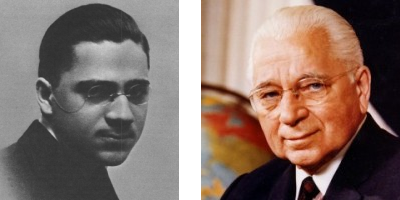

Herbert Armstrong

Herbert Armstrong

At that point Herbert Armstrong embarked on what he referred to often in later years as his “six month study” to figure out everything there was to know about the Bible. He devoured literature on doctrinal subjects published by various religious denominations, and poured over Bible commentaries and history for hours on end in the library in Portland, Oregon.

By the end of that six months, he had developed much of the idiosyncratic theology upon which the later Worldwide Church of God was built.

He was baptized in 1927, and began almost immediately preaching among the members of Ora Runcorn’s church denomination—the Church of God, Seventh Day with Headquarters in Stanberry, Missouri.

The Oregon Conference of that denomination ordained him in 1931, and he dove in to preaching at evangelistic campaigns for the denomination for the next two years. In 1933 he became part of a split in that organization which set up its headquarters in Salem, W. Virginia.

By 1934 he had developed his own special ministry—as one of the earliest “radio evangelists.”

He had his own weekly half-

In the center of the heyday of the organization’s public influence 35 years later, in 1969, the World Tomorrow radio program was on 42 major regional US radio stations, including such 50,000 watt stations as WCKY Cincinnati and WRVA Richmond. It was also on 182 local US radio stations and many foreign stations: Canada, 42; Europe, 4; Caribbean and Latin America, 21; and 1 station each in Okinawa and Guam.

A weekly half hour television program was added, and by 1969 could be seen on 17 stations in the US and 21 in Canada.

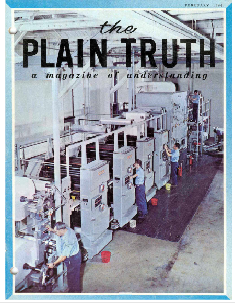

For folks who responded to his on-

For folks who responded to his on-

By the end of 1969 over 2 million copies of each edition of The Plain Truth, full-

For extensive details on the history of Armstrong’s efforts; his creation of a media empire; the establishment of affiliated church congregations throughout the country and eventually the world; the building of three college campuses where he could train men loyal to him to be ministers for those churches, as well as staff for his media empire; and more, see the major profile of the Worldwide Church of God on this Field Guide site.

The purpose of the rest of this Family Tree profile

is to chronicle the eventual break-

particularly after his death in 1986.

Continue to Tree Branches 1: The Beginning of the End

LINKS

Timeline of the history of the Church of God movement leading from William Miller up to the splits in the WCG through 2004

Researching the Worldwide Church of God under Founder Herbert Armstrong:Print and Online Resources

Extensive collection on this Field Guide site of links related to the history of

the WCG and its off-

Unless otherwise noted, all original material on this Field Guide website

is © 2001-

Careful effort has been made to give credit as clearly as possible to any specific material quoted or ideas extensively adapted from any one resource. Corrections and clarifications regarding citations for any source material are welcome, and will be promptly added to any sections which are found to be inadequately documented as to source.

Return to Top of Page and the Navigation Bar